EMDR: Adaptive Information Processing

The adaptive information processing (AIP) model was developed to explain the clinical benefits of EMDR therapy. It is the guiding principle behind EMDR’s 8-phase protocol. Although the name AIP is unique to EMDR, the terminology of neurophysiological information processing was introduced in the field of mental health in the late 1970s, with an early concept of it (without being labeled as such) dating back to early 20th century.

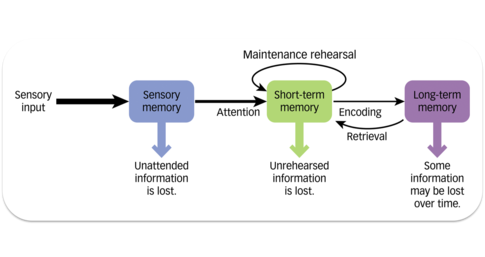

No one knows exactly how any form of psychotherapy works on the neurobiological level, but we do know that the human brain is a complex and creative information processing system. This system can be compared to other systems in the body, such as digestion and breathing, that extract something the body needs for health and survival. Across multiple stages of information processing, the brain sorts through our experiences that come to it in the form of electrochemical signals sent by the sensory organs. It also stores these experiences as memories in an accessible and useful format. Although there is not one universally accepted model of how the knowledge is organized in the brain, the AIP model is consistent with those that conceptualize memories as being grouped into networks based on their relatedness. In other words, AIP posits that neural memory networks contain thoughts, emotions, images, and sensations that are somehow related. The content of these memory networks affects us in many significant ways, shaping our attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, and emotions, as well as our perception of the world and ourselves.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

According to the AIP model, the human brain is remarkably resilient and adaptive, which is why its innate information processing system naturally moves toward mental health. There appears to be a neurological balance that allows the brain to integrate negative information while maintaining healthy mental functioning.

However, when an experience is highly disturbing, the following may happen:

- Numerous changes occur in the nervous system that disturb the neurophysiological equilibrium

- The experience is insufficiently processed due to a disruption in normal information processing

- The experience (thoughts, emotions, images, and sensations) is stored in memory networks in a way that does not allow it to connect with networks that contain healthy information that may facilitate learning and healing

- The experience is stored in the implicit emotional memory system (implicit because it does not require conscious thought)

- When a new experience that appears similar to the original disturbing event occurs (regardless of whether this similarity is real or misinterpreted), it links into the previously dysfunctional unprocessed memory network, causing the negative emotions, thoughts, and/or sensations to intensify (e.g., as in PTSD symptomatology)

- This expanding network of distress reinforces and amplifies the original disturbing experience

Here are three examples of information processing (IP). In the first example, the brain processes a negative event successfully and maintains healthy functioning. In the other two examples, something goes wrong, leaving the brain unable to complete its job.

Successful IP. Let’s say that you are an adult, and someone you know verbally humiliates you in front of others. You are disturbed by this humiliation, think about it quite often, talk about it to confidants, and perhaps even dream about it. Despite this, overall, you are still able to function normally and go on with your daily responsibilities. After a while, you are no longer as upset about it. You decide either to let it go or to have a civil, calm discussion with the individual. Regardless of how this individual reacts during the discussion, the initial distress is no longer there for you because your brain went through an adaptive information processing phase. As you processed the experience, you came to understand it better, you learned something about yourself and others, and you became better able to handle a similar situation in the future. Your brain chose the useful parts of the negative experience, learned from them, and then filed them away in a neural functional memory network along with other memories that are all related in some way.

Incomplete IP & “Small-t trauma.” The scenario is same as above, except that you happen to be someone who is extra sensitive to humiliation. There could be a number of reasons for this, but let’s say that you had a highly critical parent who often berated you, including in front of others. Although you did not suffer any extreme trauma in childhood, you were still negatively impacted by this mistreatment. (In the Phase 3 of EMDR, you [re]discover that your parent’s behavior left you with deep-seated negative beliefs about yourself, mostly around the themes of self-worth and control.) You react to the current humiliating event with strong negative feelings, thoughts, physical sensations (e.g., digestive problems, muscle tension, heart palpitations), and behavior (e.g., you may strike the offending individual or engage in self-harming behavior later on). The severity of your response is disproportionate to the severity of the event because the event triggered the unprocessed negativity from your childhood that has become “frozen in time.”

Source: Khan Academy

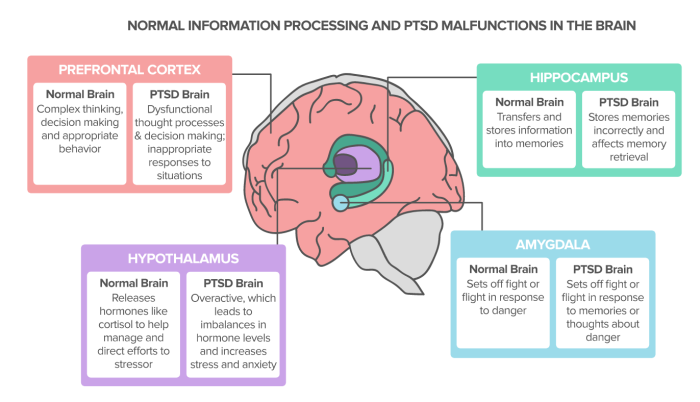

Incomplete IP & “Big-T Trauma.” The tenets of adaptive information processing model become especially clear in cases of extreme traumatic events, commonly referred to by EMDR clinicians as “Big-T Traumas.” Initial EMDR research was done with individuals who suffered from PTSD due to extreme trauma of combat, rape, and molestation. A number of participants achieved lasting relief after having suffered for years and even decades, demonstrating the unique and accelerated benefits of EMDR.

The diagnostic criteria for PTSD (found in the DSM-5) include a description of traumatic events that precipitate PTSD. This information reads as follows:

You have been exposed to a traumatic event that was actual or threatened death, secual violence, or serious injury, in one or more of the following ways:

- Directly experiencing the event (it happened to you)

- Directly experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to the details of the event (e.g., first responders collecting human remains, police officers repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse)

- Witnessing the event in person as it occurred to others

- Learning that the event occurred to a close family member or close friend (in this case, actual or threatened death must have been violent or accidental)

EMDR to the Rescue

As mentioned above, we do not have scientific proof of how exactly EMDR is able to alleviate psychological suffering. Researchers who support the AIP theory behind EMDR believe that the procedural elements of the EMDR protocol, including the bilateral dual attention stimulation, trigger a neurophysiological process that allows for the normal information processing to resume.

Specifically, it is currently hypothesized that by directly processing the disturbing information through dual attention, EMDR does the following:

- Establishes a link between consciousness and the memory networks where the disturbing information is stored

- Facilitates memory retrieval and the recognition of true information

- Creates new neural pathways and the ability to access unprocessed disturbing events

- Moves the disturbing information—at an accelerated rate—further along the appropriate neurophysiological pathways until it is linked with neural networks that contain positive information the person needs in order to store the original memory with appropriate emotions and adaptive beliefs

- Helps the brain transform all aspects of the disturbing memory, including perceptions, emotions, and sensations

- The information shifts from implicit/nondeclarative memory (does not require conscious thought) to explicit/declarative memory