Depression

What is (unipolar) depression?

Depression is a serious but treatable mood disorder experienced by approximately 1 in 10 U.S. adults. It can happen at any age, but often the symptoms begin in the teens and the 20s. Children can also experience depression.

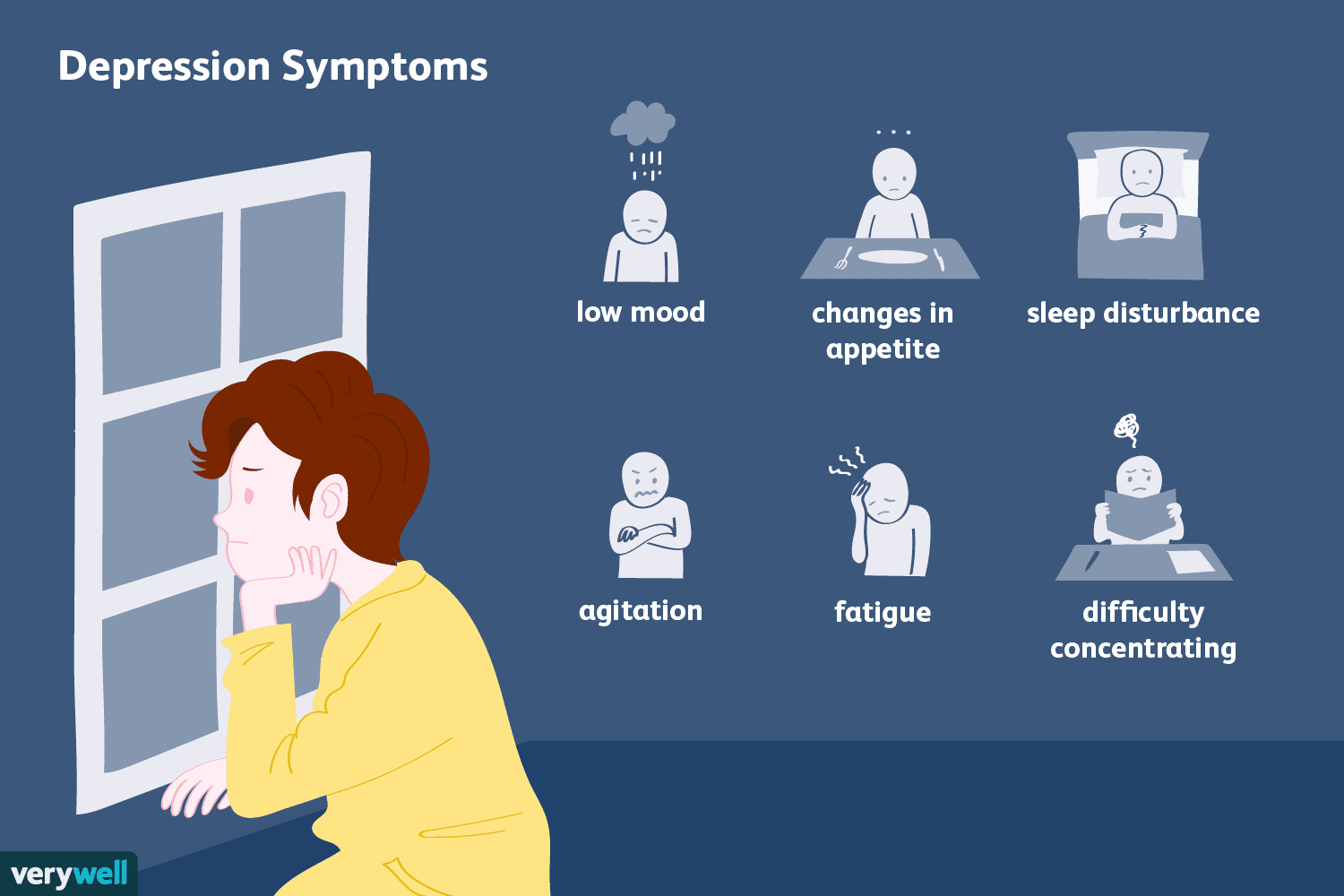

Depression affects how we think, feel, and handle daily activities. It interferes with our ability to work, study, care for children, eat, sleep, and enjoy life. While most people think of depression as sadness, there are many other possible symptoms.

Gender and age

Women are up to three times as likely to develop depression, beginning in early adolescence. Typical symptoms for women are feelings of sadness, worthlessness, and guilt. This does not mean that women cannot experience any of the other criteria for MDD. Also, see above for depression types specific to women (MDD With Peripartum Onset, Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder). Lastly, while not listed in the DSM-5 as a codable diagnosis, it is not uncommon for women who are transitioning into menopause to experience depressive symptoms due to significant hormonal and other physiological changes that occur during the perimenopausal time in their lives.

Men who are depressed are more likely to feel angry, aggressive, irritable, restless, or “on edge.” They may also feel tired and lose interest in work, family, or hobbies. Men are also more likely to engage in reckless behavior, including drug and alcohol abuse. Since they are less likely to be aware of and seek help for emotional symptoms, men may present at a doctor’s office with physical symptoms that can be indicative of depression, including accelerated heart rate, tightening in the chest, headaches, and digestive problems. While women are more likely to have depression and to attempt suicide, men are more likely to die by suicide because they tend to choose more lethal methods.

Children may be irritable, pretend to be sick, experience frequent physiological symptoms such as unexplained stomachaches or headaches, refuse to go to school, misbehave (out of character), isolate, cling to a parent, or express worry that a parent may die (seen especially in younger children). A teacher may report that the child does not seem like him/herself. Depression in children may also begin as high levels of anxiety. If there is no treatment, both or one of the disorders may become chronic. Since children often don’t know how to label their thoughts and feelings, it is important to seek an evaluation by a mental health professional who specializes in the treatment of children.

Teens and young adults are in the age groups when depression is most likely to first occur. Physiological changes are taking place, including the final stages of brain development, and identity is being formed through an often confusing and challenging process. There is also emerging sexuality and having to make independent decisions for the first time. Common signs of depression for this population are feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, guilt, loss of interest in activities previously enjoyed, increased anxiety, eating disorders, or substance abuse. Depression is the most common health problem among college students.

Older adults are likely to go through a lot of changes. Examples are retirement, health issues, financial difficulties, death of loved ones, and having to leave one’s long-term home. Among risk factors for depression in older adults are being female, having a chronic health problem or disability, being lonely or socially isolated, and misusing alcohol or drugs. Since older adults are likely to be on various medications and have other medical problems, it is important to rule out depression as a side effect of a prescribed drug or as associated with conditions such as stroke, brain injury, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, a neuroendocrine problem, or multiple sclerosis.

Risk factors for depression

As with most mental health disorders, researchers still don’t know what exactly causes depression. Most likely, it is a combination of “nature and nurture” factors including genetic, neurobiological, physiological, environmental, and psychological factors.

Temperamental. One of the better-established risk factors is the personality trait called “neuroticism” (based on the Five-Factor Model, which is the most widely accepted theory of personality to date). Those individuals who score high on neuroticism are more likely to develop depression in response to unfavorable life events.

Genetic. Individuals with a parent or a sibling who has depression are two to four times more likely to have it as well. Heritability has been shown to make up about 40% of what causes depression, with the personality trait neuroticism accounting for a substantial portion of it. Particularly vulnerable to depression are those with first-degree relatives who had severe depression that began before age 30, especially if those relatives were female.

Environmental. While stressful life events may precipitate onset of depression, they have not been determined as reliable in predicting who will and will not experience depression at a clinical level. So-called “adverse childhood experiences” (ACEs) have been shown as the most potent environmental predictor of depression. ACEs can come from different sources, including family of origin, peer group, and society in general.

Psychological & Physiological. The presence of other mental health issues, such as anxiety, substance dependence, or personality disorders (in particular Borderline PD) increases the risk for depression. Likewise, when compared to medically healthy individuals, those suffering from chronic or disabling medical conditions are more likely to develop depression and have their depression become chronic.

If you are in a crisis

- Call 911 or go to the nearest hospital emergency room

- Call the Georgia Crisis & Access Line at 1-800-715-4225

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255)

If someone you know is depressed

- Be supportive and patient and offer to listen to and spend time with them

- Invite them to activities; don’t push too hard if they say no, but continue to extend invitations

- Suggest getting help and remind them that with time and treatment, things will get better

- Don’t tell them to “snap out of it,” “just be positive,” or that they “just need to try harder”

- Remember that depression is a medical condition, not a character flaw or a sign of weakness

- If you think your child/teen may be depressed

- Remember that your children depend on you to recognize their suffering

- Keep an eye out for changes from usual behavior and consider how long such symptoms have been present, how severe they are, and how different the child/teen is acting from his/her usual self

- If your child/teen confides in you, do not discount or ridicule expressed feelings/thoughts you believe to be unrealistic or exaggerated; instead, validate while also pointing out realities and offering hope

- Do not ignore comments about suicide

- Remember that depression often persists, recurs, and may continue into adulthood, especially if left untreated; if you suspect depression in your child/teen, address it right away

Content based in part on the following two public domain sources:

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013

- National Institute of Mental Health publications